Podcast: Play in new window | Download | Embed

Subscribe: RSS

Today I’m proud to have Scot McKnight with me on the podcast.

Scot is a recognized authority on the New Testament, early Christianity, and the historical Jesus. McKnight, author or editor of forty books, is the Professor of New Testament at Northern Seminary in Lombard, IL. Dr. McKnight has given interviews on radios across the nation, has appeared on television, and is regularly speaks at local churches, conferences, colleges, and seminaries in the USA and abroad. Dr. McKnight obtained his Ph.D. at the University of Nottingham (1986).

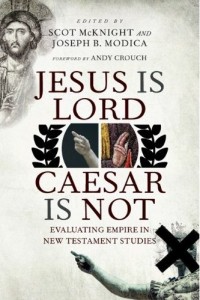

Scot sits down to talk about Jesus Is Lord Caesar Is Not, which he edited with Joseph B. Modica.

As the tagline infers, the book is an evaluation of Empire Criticism in the New Testament. For those unfamiliar with Empire Criticism as I was before reading the book, it can defined as an approach to New Testament studies whereby the New Testament’s message is seen primarily as a criticism of the Roman empire.

I loved every second of this interview with Scot, and was especially struck by this statement…

“There is politicization…. Young evangelicals have become progressives… Progressives today are socially active, believing that the way to make society better, so for instance the aim is the common good, the aim is repairing the world, the aim is to be significant in the world and make the world a better place, the aim is socio political, and means is socio political, namely they see themselves as repairing the world by becoming involved in social justice, that is a fundamental politicization of discipleship in the church and Christianity, in fact so politicized is it that many of these young progressive evangelical type Christians and non-evangelical type Christians have very little to do with the church… it’s a progressive posture in our culture on the part of Christians where they see their fundamental task to work for the common good by providing water, helping to end sex trafficking, etc., all of these things are good, but they are divorced from the church and they are anchored in the actions of politicians in Washington DC and Berlin and London, these become the central focus and when that happens we do exactly what happened when Gustavo Gutierrez was arguing in the 1970’s and 80’s that the church has to be de-centralized, so what we have I think is a colossal politicization of the church in our world today and it is impacting the church in ways that I think could be remarkable.”

Please go and hear this for yourself in the context of the entire interview! Then come back and tell me what you think about what Scot said.

Be Sure To Subscribe To the Email List & Never Miss a Post or Podcast

Wow, you weren’t kidding about him dropping a bomb there. If your unpacking of his statement at the end of the podcast was on target, then I may agree with the principle behind what he said, but it sounds like he has serious disagreements with N.T. Wright on the topic of the Kingdom as it relates to God’s will being done on earth as in heaven. I’m heavily informed and influenced by Wright myself, and am of the leaning that wherever God’s will is done on earth as in heaven, the Kingdom is present, and is thus never fully divorced from the work of the church, regardless of whether the actors actually lay claim to that fact. Your reference to Gandhi’s efforts and others outside the scope of Christianity proper come to mind here. In my view, Gandhi was absolutely doing Kingdom work.Viewing Prof. McNight’s comments from another angle, however, I have personally noticed a neglect of internal church needs, where, for example, the church will send volunteers into the community as mentors and tutors, or support local ministries in feeding homeless people, or give financial assistance to foreign missions, but when a family within the church experiences a job loss and can’t make their mortgage payment, the response is, “I’ll pray for you.” I see this as a result of lopsided priorities, and in a sense, an embrace of social efforts that are divorced from the church in that they are undertaken either at the expense of or with an intentional or accidental negligence toward the basic needs of those within the church community. This should not be, and if I understood this point correctly within what McKnight was saying, then I totally agree.

@JR Buckley @trischagoodwin Yeah I think there’s a lot to consider here. I think I agree with Scott that there is something wrong when we divorce our good works from the church. To what you were saying JR about churches working to help those outside and neglecting those inside, further than that, what I often see and I think what Scot was speaking to, are these people, who, yes very often would fit the mold of young progressive evanglical, belong to no local church, and don’t love the church, but have decided to be a solo Christian and thus go out and do these good works but make no connection between them and the church.I think where I might have a hard time agreeing with Scot, is in what it means to be under the banner of the church. If we do good works for the Kingdom and because of the Gospel then the outward action might look the same as someone not doing it for those reasons, but the motivation in our hearts is what makes the difference. For instance, my local homeless shelter paired me up with a gentlemen who was homeless but has been put into an apartment and now support is important so that he doesn’t return to the streets. This isn’t a program that my church launched, but If you asked me why I’m doing that I will point to my belief in the Kingdom, but outwardly it looks the same as someone who might be doing it for the “greater good” that Scot talked about. Now, Scot might say the same thing, and agree with me, but because we didn’t have time to go into that, I don’t know.

A lot of us came from a church context that said we can’t just go and spend time with people who don’t know Jesus at a coffee shop down the street, but the church had to open it’s own coffee shop, a “Christian” coffee shop, whose coffee sucks and they close at 6pm. And we can’t just go and join in the good works at the downtown soup kitchen, but we have to open our own food pantry and it has a fraction of the food and infrastructure of the existing food kitchen, but this way we don’t have to rub shoulders with those liberal activist types down town and our church gets the credit for it. Again I don’t know what Scot would say to that, but I don’t think that’s what he’s advocating.

This is thought-provoking, exploring some topics that haven’t yet found their way into my studies; thank you for covering this book/author in your podcast. I’ve certainly noticed themes of Empire Criticism in some of my reading, but wasn’t familiar with it by definition.

I do agree that there has been a “politicization,” but I’m not sure I agree with the way Scot presented it. I think that when the motives behind our “common good” activities are on being “significant” in the world or on pursuing “success in our culture” (even if the cultural circles we participate in are ones that promote social justice), that is where lies the danger of impacting the church in ways that are detrimental.

I believe the Kingdom is more inclusive than exclusive. If the activities we pursue to work for the common good are outside the confines of The Church, but are not excluding of The Church, that is more the example of Christ than restricting our efforts to only activities within the community of The Church. I would argue that if the motives behind such work are to bring the Kingdom to everyone and not for the goal of being significant or culturally (or politically) successful, then there is no issue with doing these activities outside of The Church.

Shane Blackshear I’m surprised that there was so much shock around this. For awhile now, Scot’s been identifying as an Anabaptist. To me, the key idea of Anabaptism is church-as-counter-society. In this mode of thought, the church does not work for justice in the world, it provides an example of how the world could be if there was justice. For example, another Austin friend, Josh Hostetler (http://twitter.com/amishhipster), grew up among the Pennsylvania Amish, and would tell you he’s never seen a homeless Amish person before.

David E Fitch and Geoff Holsclaw (neo-anabaptist, also at Northern Seminary) tell a fascinating story in their book about why their Church decided it might not be their call to build wells in Africa. (When are you getting them on the show?) I’m proud to be a part of Vox Veniae , a church that decided the best way to address the issues we saw in the world was to be good neighbors to those who were struggling with those issues. That meant relocating, that is, sacrificing comfort for incarnational mission.

@ChrisMorton82 I wasn’t aware that this was a trait of Anabaptism per se. I lean very Anabaptist so I guess I’m surprised by myself not latching on this more quickly.

I think I’m anxious to explore this idea more. I’m mostly curious to know if Scot and others like him are advocating for works of justice to be done exclusively (or more exclusively) BY the church or for those works to be done only WITHIN the church. There’s a lot of scripture that I would have to work through and rethink. For instance Jesus’ words about seperating the sheep from the goats ” 35 For I was hungry and you gave me something to eat, I was thirsty and you gave me something to drink, I was a stranger and you invited me in, 36 I needed clothes and you clothed me, I was sick and you looked after me, I was in prison and you came to visit me.”Are we only suppose to do these things AS a church, or only for people INSIDE our church? Also, what about the good Samaritan? Just a few things off the top of my head that I’m thinking through.

You spoke about Vox deciding to be a good neighbor. I know this happens, and I love it, but to whom are they being a good neighbor. I would assume that would be to people outside of your church body. Is this so different from building wells in Africa? What I mean is, if Vox’s neighbors needed water, you might think that being a good neighbor involves helping them get it. So it seems like the only difference is geography. Obviously it’s not wrong to decide that building wells in Africa is not what God is calling your church to, but that’s not to say that it’s not what any church should do. I’m just thinking this through. We should get coffee soon and talk about it.

Also, I’ve been talking to geoffholsclaw about coming on the podcast and I expect it to happen soon.

Thought-provoking content. Technical problems are distracting, i.e. sound only in left channel. Please produce in mono to avoid this. Thanks.

@Gerald Iversen Thanks for listening! All episodes (except for a few produced early on) are done in mono. It might be something with your ear phones.

A couple of notes:

– This podcast was only in the left channel, I am sure there was a simple mistake somewhere in the production process. You recorded it in mono and somewhere along the way you mixed it down stereo. It seems like you fixed it in subsequent interviews though.

– This was a great interview. I heard Horsely speak a few months ago at APTS. I tend to think he’s on to something, and that Jesus was critiquing power of all kinds all of the time (whether it be Rome or the Jewish religious leaders).

– I’ve always thought McKnight and those who have critiqued Empire Criticism haven’t done a good enough job in differentiating our context from that of the early Christians under Rome. Or at least in making sense of the distinctions helpfully. I mean, they’re scholars and I’m just some dude, BUT while a fully fleshed out Empire Criticism was not recorded explicitly in the scriptures, it was implicit in everything that happened (as he admitted).

While I agree with his idea that we are to grow the Church despite what ever our governing situation, we are in a historically rare setting whereby we govern ourselves. I think he was also wrong when he said that we are missing the point when the Church tries to act for the ‘greater good’ rather than the Good of the Church or God’s kingdom (which he rightly distinguishes between). He is correct to say that Christians hopes are often socio-political in scope simply because we live in a time when that’s possible. It simply wasn’t then, and quite frankly they never dreamed a situation like ours could possibly exist.

To me it seems he’s (over)reacting to some on the religious and political right who try to legislate a Christian ethic and moral code upon a pluralistic nation. I tend to think that, despite his wide cast of contributors to this book, they overstate the application of their findings.